What a game. This series has been so hyped that a scoreless tie through four innings felt like a letdown. But then the party got started. In the end, we got everything we wanted: stars, steals, defensive gems and gaffes, and even a walk-off home run to evoke Kirk Gibson. But my beat is writing about managerial decisions, so let’s get a quick 1,100 or so words in on that before it’s time for Game 2. Specifically, I’m interested in the bottom half of the 10th inning in Game 1 of the World Series, and the decisions that led to Freddie Freeman’s colossal walk-off grand slam and lifted the Dodgers to a 6-3 win over the Yankees.

Using Nestor

Hated it. The pitch for why it’s a bad decision is pretty easy, right? Nestor Cortes hadn’t pitched in a month, a trusted lefty reliever was also warm, and the scariest possible guy was due up. It’s hard to imagine a scenario where this was the lowest-risk move. There’s not much I can say about the pitch-level data, because he threw only two pitches, but there are myriad reasons to opt for a reliever over a starter in that situation.

A lot of Cortes’s brilliance is in his variety. He throws a ton of different pitches. He has a funky windup – several funky windups, in fact. He changes speeds and locations. That’s how a guy who sits 91-92 mph with his fastball keeps succeeding in the big leagues. But many of those advantages are blunted when you don’t have feel for the game.

Both of the pitches that Cortes threw were fastballs in the strike zone. What did you expect? He hasn’t thrown in a game in a month, and starters have trained their whole lives to start with fastballs. That makes sense because the game starts in a low-leverage state. Cortes came in with the tying run on second base and the winning run on first.

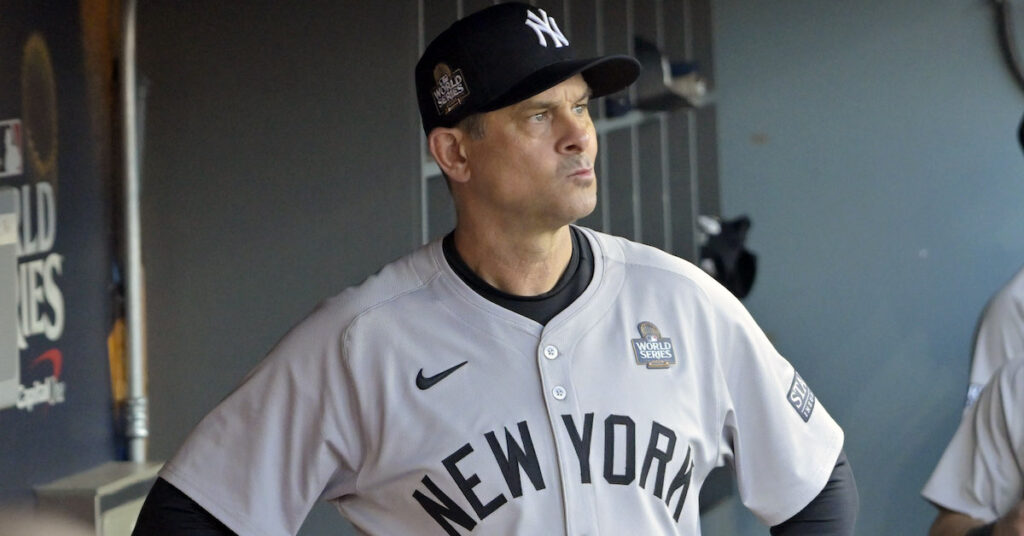

This is a feel decision in the end, and Aaron Boone obviously has a lot more feel for his team than I do. But I can’t shake memories of Michael Wacha coming out of the Cardinals bullpen in Game 5 of the 2014 NLCS — and I’m not the only one who saw shades of that fateful decision in this one. After having missed most of the second half of the season with a stress fracture in his right scapula, Wacha made his first appearance of that postseason with the score tied 3-3 in the bottom of the ninth and his team on the brink of elimination. He looked off, Travis Ishikawa walked it off, and the rest was even year history. I think Cortes is going to be an important contributor for the Yankees this World Series – but I would not have chosen this spot for his return to the mound.

Walking Mookie

I don’t hate it. To set the situation, the Dodgers had runners on second and third with two outs, trailing by one. Mookie Betts was due up, and Freeman was on deck. Boone walked Betts to bring up Freeman, setting history in motion. But should he have walked Betts?

Generally speaking, walking the bases loaded isn’t a great idea. It makes it far too easy to drive in a run with a walk or hit by pitch. Our WPA model thinks that decision cost the Yankees about three percentage points of win probability. That’s a really big swing for a managerial decision; most of the ones I go over here are in the sub-1% range.

That’s the general case. However, in this instance, we have to consider the players involved, and that goes a long way toward making Boone’s decision look better. First, I modeled Betts against Cortes. Betts has fairly close to league-average platoon splits over his career. Cortes is fairly close to average, too. But “league average” is a bad deal for a lefty facing a righty, because righty batters do well against lefty pitchers. Chuck their projections and regressed platoon splits into a model, and I get a projected .395 wOBA, which is pretty close to Betts’s career numbers against lefties.

What does that mean in terms of winning the game? If I throw a completely normal lineup in after Betts, and tell my model the Yankees pitched to him, it spits out a 26.2% chance of the Dodgers winning the game. Our win probability model, which doesn’t have any information about the identity of the batter and pitcher and instead just uses league average, gave the Dodgers a 23.7% chance to win at that juncture. Betts against a lefty: good matchup!

That’s not quite right, because there isn’t an average lineup after Betts, but let’s skip ahead and see how the Freeman/Cortes matchup projected with the bases loaded. Freeman has huge platoon splits across an enormous sample; in his career, he’s been 14.1% better against righties (.397 wOBA) than lefties (.348). Even after regressing his splits a bit back toward the mean, he’s a great hitter against righties and meaningfully worse – though still great – against lefties.

When I plug the Freeman/Cortes confrontation into my model, I get a meaningfully lower projected wOBA – .373 – than the Betts/Cortes clash. Add in the game state, and I had the Dodgers with a 28.8% chance of winning when Freeman stepped to the plate with the bases loaded.

Just one last step to do in our math – we need to go in and change Betts’s odds to account for the fact that Freeman was batting behind him, instead of some chump. That bumps the odds up to 26.7%. As my math consultant Count Von Count would tell you, 28.8 is larger than 26.7. But there’s a confounding variable: Freeman is hurt. He carried a 37 wRC+ across his 33 plate appearances heading into the World Series, and he’d missed four of his team’s 11 playoff games with an ankle injury.

Our projections don’t know anything about Freeman’s health. If he were actually the hitter he’d looked like in the NLDS and NLCS, that would change the matchup completely. Then we’re talking about more like league-average protection for Betts. That would tell you the Dodgers had a 26.7% chance of winning the game when Freeman batted, assuming he was the diminished model of himself.

The decision is too close to call, in other words. Now, with Tim Hill in there, as I would have preferred, things would have been different. Hill is a lefty specialist with huge platoon splits. I wouldn’t let him near Betts with a 10-foot pole. But Cortes is far less specialized; he’s pretty good against everyone. That’s the difference in situations as close as this.

To wrap things up, I would not have used Cortes in the bottom of the 10th. If I did, however, I probably would have pitched to Betts, but I think it’s a close enough call that either decision is defensible. If the Yankees had instead gone with Hill, and still ended up with runners on second and third and two outs, I definitely would have walked Betts to face Freeman. And of course, it’s always worth mentioning that all of these decisions had tiny overall effects on the outcome of the game. Boone might have moved the Yankees’ win probability by a few percentage points with his maneuvering. Freeman moved it by 72-ish percentage points with one swing. The players always determine the outcome, much as we like to rehash managerial decisions.